|

During my first year of teaching in a first grade classroom, I had an unforgettable experience. Two vivacious first grade

girls had been struggling for months trying to learn how to read. Then one day in February, the light turned on in their minds. Things started clicking. They had been crawling at a snail’s pace but suddenly they were

soaring. This was one of the reasons I decided to teach my children at home—I wanted to be the one who was there to experience each leap in understanding as it occurred. What is more exciting than watching your child

learn to read? On the other hand, it may be intimidating to feel the responsibility of helping your child with this most important academic skill. From my three years as a first grade teacher (set your mind at ease—an

innovative teacher), from the research I’ve done over the years, and from the opportunity to learn from our home school experiences over the past eleven years, I have some thoughts to share. A --Read Aloud. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that once your children know how to read that you should stop reading aloud. I remember my elementary

teachers reading aloud to the class but it didn’t profoundly affect me until my sixth grade teacher read B -- Don’t Rush Academics.

Ruth Beechick calls this “the optimum learning time.” She says if we wait until the child shows readiness and interest, the child will learn faster and easier. In her excellent book, Follow the child’s lead; instead of pushing, let him come to you with questions or

discoveries. At age two, my daughter was delighted with her magnetic letters. She’d spend hours at her little desk often asking me what a certain letter was. By age four, she knew most of the sounds, because of her own

motivation, so I thought she would be an early reader. Surprisingly, things didn’t “click” for her until she was almost eight. Even though she had the tools, she didn’t have the maturity or motivation to master reading.

There is more to reading than simply knowing phonetic sounds. Phonological awareness is an important pre-reading skill to acquire. This is oral

work that precedes phonics. (Phonics combines the letter symbol with the sound.) Phonological awareness appropriate for preschoolers includes: hearing syllables, rhyming, alliteration, blending parts of a word together (example: parent says /d/ ... /og/ and child guesses “dog”).

C -- Help Your Child Understand Print. Predictable books are stories where the child can easily guess the text of the book because of a pattern, a rhyme, and/or the illustrations. Perhaps do an activity below

once a week in the early stages of learning to read. Or simply enjoy reading predictable books together every day. Print out songs and sing them, pointing to the words as you go. Write a familiar predictable story or

nursery rhyme on a chart. Make three copies of it. Let your child become acquainted with the chart by reading it to him, reading it together, and allowing him to explore it on his own. Then help your child cut a copy of

the chart into sentence strips. He can place the strips on the corresponding sentences on the chart. Or he can arrange them in order (or a silly order) without the chart. Later, help him cut the third chart into word

cards. He can match the words onto the sentence strips or the story chart. Or he can make up original sentences from the word cards. These kinds of experiences help children realize that the whole is broken down into

sentences, then into words, then into sounds. This is called global learning or learning from the top down; experts claim it is the way most children learn. Charlotte Mason, always ahead of her time, recommended a very

similar approach for teaching reading. In volume one of her series, she wrote of using ‘Twinkle, Twinkle’ and ‘I Love Little Pussy’ and word cards for learning to read. Several times during the school year, I would

post a large chart of a song we had learned together somewhere in the classroom. I wouldn’t mention it but quietly watched as the students discovered the new addition. One of the better readers would usually figure it

out first. Then even the nonreaders would go to the chart, point to each word, and “read” it since they, too, knew the song. These types of activities start with what the child already knows, a nursery rhyme or song,

and reinforce the concept of print. Children may need successful experiences like this throughout the sometimes long and frustrating road to becoming an independent D -- Teach the Code. “[This method] has been researched and proven to work on children age four to adult

nonreaders. It takes what the child knows, the sounds of his language, and teaches him the various sound pictures that represent those sounds.” By sound pictures or symbols, the Another book to consider purchasing is

E -- Sight Words.

Charlotte Mason stressed the importance of habits. If a child spells a word wrong, it may become a habit. Hindsight has shown me that invented spelling is not the best approach with

these irregular words. Be thorough by teaching your child to spell each of these “weird words” and reviewing them often as they come up in his writing. F -- Fluency.

Echo reading is wonderful for fluency. I like to do this on material that is slightly above the child’s comfortable reading level. Use scriptures and great children’s literature that is not

predictable for echo reading. Sit close together so you can both follow along in the book. The parent points to each word as parent and child read aloud together, pausing very slightly after

each phrase. Sometimes the parent will read a split second after the child, echoing him on the easier parts. Sometimes the parent will take the lead so the child is echoing the parent through

the difficult parts. Echo reading helps greatly with fluency and expressive reading.

G -- Give Your Child Time to Read on His Own. H -- Home: A Writing-Rich Environment.

My children have all enjoyed writing before they learn to read. They ask how to spell certain words to make their own notes or they write a list of all the names of people in our family and

extended family. Let children see you writing. Try having written conversations with your children. An early attempt might require only yes and no answers from the child. This may

evolve into daily letter writing between family members to express feelings and work out problems. Use patterns from predictable books to inspire original works. For example, after reading The

Bug in the Jug, my then five-year-old daughter wrote and illustrated a book. It reads:

“This is a sheep. This is a jeep. This is the sheep in the jeep. I -- Use Real Books for Your Reading Program. J -- Relax and enjoy!

Watching our own children learn how to read is a memorable event. Because of our decision to educate our children at home, we are present to experience the light turning on. We see

things starting to click. How thrilling to observe a tentative reader turn into an avid one! Let’s soar with our children into the fascinating world of reading. Silly Sentences: A Mix-and-Match Manipulative Reading Activity

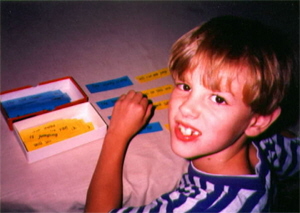

Silly Sentences provide fun practice with the three levels of code presented in Reading Reflex.

This game is an enjoyable, homemade addition to your beginning reading program. This activity involves your child physically as he manually places two sentence parts together.

Think of Silly Sentences as a reading manipulative. It involves chance and humor; we often chuckle together after reading a Silly Sentence. And the outcome is different each time you

play. This game also works for an older child who may need a review of phonics but would be offended by a more "remedial" method. Even after my daughter was an excellent independent

reader she would occasionally play Silly Sentences just for fun. In the game, the child forms sentences by placing a beginning and an ending together. Here's

an example of a couple of Silly Sentences placed in a logical arrangement:

The red brick is here. Now, if your child happened to mix and match the sentence parts differently, he would end up with a sensible sentence and a ridiculous sentence:

Glen is here. I imagine this animated scene in my mind: a smiling brick, wearing red sneakers on the end of his skinny stick legs, jumping about wildly. Pretty hysterical!

To make your Silly Sentences game, highlight and copy the

Print out the sheet of sentence beginnings on one color of card stock and print the sheet of sentence endings on a different color of card stock. Choose pastel shades so the print shows

up clearly. After laminating the sheets, cut into phrases using a paper cutter. Or, you may cut up the sheets you print on regular paper and glue them each to a slightly larger strip of

construction paper or card stock (one color for beginnings and another color for endings) and laminate. You may store the sentence beginnings in one envelope or zip lock bag and the endings in another.

Once your game becomes too easy for your child, it's time to make the next set of sentences. Set aside a little time to make these inexpensive, colorful manipulatives. Then let your child

mix and match his way to fluent reading with Silly Sentences--and enjoy a few chuckles together along the way. Recommended Reading for Parents: Return to |

|||